|

©1999-2015 |

The following article appeared in WPA Press, Vol. 9, July 2001.

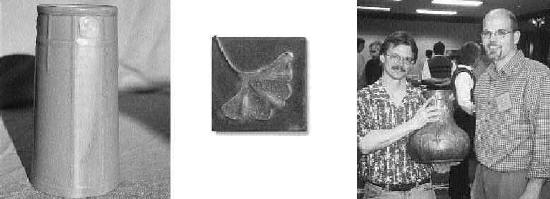

Ephraim Faience Pottery “I grew up on a farm and wanted to get as far as possible from clay and dirt,” says Kevin Hicks of Ephraim Faience Pottery. Yet here he is, five miles from civilization on a soybean farm in rural Wisconsin, with deer, pheasants, woodchucks and other sundry wildlife all around. The twist is, the barn houses an Arts and Crafts pottery that represents Hicks’ own mini rebellion against industrialization. He and partner Scott Draves met while working in a commercial pottery turning out salt-glaze wares at a frightening rate. Hicks had held several positions at the pottery while completing his art and business degrees, but it wasn’t until he became a potter there that he really felt the full effects of commercialization— the same mind- and bodynumbing automatization that led to the Arts and Crafts movement. “I was being turned into a machine,” Hicks says, “throwing a coffee mug every minute or two, all day long. We’d turn out hundreds a day. We couldn’t make anything that would take more than five or ten minutes to throw. Scott and I would talk about how we longed to work on art pieces like the turn-of-the-century ceramics he collects. Scott Draves came to ceramics from an even more circuitous route. He’d worked as a test-equipment designer in the avionics field until he knew it was time for a career switch. Decorating art pottery seemed like an odd segue, but he found that his precise technical skills were well suited to the new profession. “I was the fastest decorator they had,” Draves says. “I could paint on blue or green slip flowers or birds in 15 seconds. By the end of the day, there’d be 450 mugs done in different patterns. I did that for 10 years. At the same time, Draves was collecting Arts and Crafts pottery, none of which costs more than $80 in those good old days. “I also had a business buying, repairing and selling oak antiques—oak is king around here—including quite a few Mission-style pieces. And I saw how Arts and Crafts pottery was appreciating: an $80 vase was now going for$300, and I knew that working in that style was something Kevin and I could do. So in 1996, Hicks and Draves began developing the forms, designs and glazes that would become Ephraim Faience’s pottery line. The lived off their savings in order to be able to work full time on the pieces, and enlisted a knowledgeable friend with an extensive Arts and Crafts collection to function as a design critic. They’d take their latest designs over for his inspection, and tweaked their products until he agreed that they’d really captured the essence of the style.

The pairs’ big break came in Asheville at the 1997 Grove Park conference. “Lee Jester [of Berkeley’s The Craftsman Home] suggested we bring some pots down to show him,” Draves remembers. “It was14 hours away from Madison, Wisc., but we were game so we loaded up the car and drove down. We had a general description of Lee, so we sat in the lobby of the Grove Park Inn watching for him. In 20 minutes some 100 people must have come up to us, wanting to know where we got those ‘Grueby’ pots. We went out to the car to get more, and the crowd just swarmed around our trunk.” Ephraim Faience Pottery— whose name is derived from a small town in the “thumb” of Wisconsin, and the name for earthenware with opaque glazes—took off in a big way from there. Word-of-mouth business, and catalog, website ( www.ephraimpottery.com ) and Arts and Crafts show sales are brisk. About 80 percent of their orders are in the matte green glaze commonly associated with period pottery, though Draves, who is the glaze master, professes a personal fondness for their yellow pieces. Hicks and Draves push to keep the company’s line evolving. They never produce more than 500 pieces of any vase, and periodically retire items as they near that cutoff, or when they introduce new wares. Each piece is hand thrown and designs hand sculpted—usually by Hicks—then dried for 3 to 10 days, bisque fired, glazed and fired again. Excess glaze is ground off the bottom, and only then is the piece ready for the customer. Draves estimates that preparing products for each Arts and Crafts show takes two weeks, with another week spent commuting to and from the location and actually manning the booth. This year, he and Hicks and marketing manager Kristin Zanetti have one show per month on the schedule. Zanetti and Jesse Wolf, who takes care of shipping out products, also have creative input. Zanetti says she was given “homework” over the Christmas break one year: design a gingko leaf tile. She put her art background to work and came up with Ephraim Faience’s popular Nostalgia and Gingko tiles. And Wolf, the newest addition to the group, is decorating tiles and has shown Draves some prototype pots that just might be in the next catalog. The most important thing for us is to keep pushing ourselves to take on new creative challenges,” Hicks says. “There’s a huge, wide world of Arts and Crafts,” Draves agrees. “After working a 12-hour day for three weeks straight getting ready for a show, we may be filthy and tired, but we’re certainly not bored.” This article first appeared in American Bungalow magazine (Fall 2000, Number 27), a quarterly publication devoted to the Arts and Crafts movement and early-20th-century homes. For information, visit www.ambungalow.com. The WPA Press thanks American Bungalow for permission to reprint this article. WPA Related Pages: |